(前記事より続く)

旧約聖書に感じる私たちとのつながり

[toggle]One of the ways the Old Testament brings comfort to the anxious is by its dependence on two personable literary genres. The first is historical narrative, which is found in books like Genesis or Joshua. Unlike some social media profiles that are carefully crafted to present only the best, most exciting, and successful sides of a person, these narratives reveal a more complete picture. Characters are presented with both achievements and frailties. There is Moses, the scared speaker (Ex. 4:10); Ahaz, the desperate monarch (2 Kings 16:7); and Naomi, the bitter mother-in-law (Ruth 1:20–21). These characters remove the stigma of anxiety and remind us that God works through broken people.The Psalms complement the narratives by offering snapshots of individuals responding to anxiety. Rather than a tidy summary packaged for retrospective sharing, David’s penetrating question, “How long, Lord?” (Ps. 13:1), invites us into his active suffering and gives us permission to plead with God to end our suffering, too. Asaph expresses the inexpressible when he says that God has given him only “the bread of tears” (Ps. 80:5).

Most importantly, this group of human voices provides theological solutions: “The Lord is with me; I will not be afraid. What can mere mortals do to me?” (Ps. 118:6). The comfort of the Psalms is especially felt by recalling that they are songs meant to be sung and they are the inspired Word of God. This means, as John Calvin noted, that when we sing the Psalms during trials, it is as though God’s Spirit is singing through us.

Of course, the texts of the Old Testament don’t always seem like a good resource for fighting anxiety. There are moments that feel like a literary gut punch, including Micah’s promise of judgment on the people of Israel (Mic. 2:3–5), and stories of severe testing, such as Abraham’s near sacrifice of Isaac (Gen. 22:1–18). Far from comforting us, these texts only increase our anxiety. But if we read them closely, we find that each story is redemptive because the anxiety is momentary and meant to draw us closer to God in faith and hope. It’s never the intent of a biblical author to constantly tease a believer’s fears or to pry away their faith in a good God. [/toggle]

旧約聖書は、2種類の文学形態を用いて私たちの不安を慰めてくれる。

一つ目は創世記やヨシュア記のような歴史物語だ。

現代の人々は自分の良いところ、成功した部分だけをソーシャルメディアで見せびらかそうと躍起(やっき)になるが、聖書の歴史物語は人々の偉業だけではなく、その弱さをも伝えている。

人前で話すことを怖がるモーセ(出エジプト4章10節)や絶望に打ちひしがれるアハズ王(列王記下16章7節)、ふてくされる義母ナオミ(ルツ1章20–21節)など、旧約聖書の登場人物は不安感についての思い込みから私たちを解き放ち、「欠けのある人々を用いて神は働かれるのだ」ということを思い出させてくれる。

もう一つは、不安感に対する人々のリアクションを描くことで、こういった物語を補足している詩篇のような文学形態だ。

旧約聖書は過去を振り返って理路整然と描かれた要約文ではなく、「いつまで、主よ、わたしを忘れておられるのか。」(詩篇13章1節)と鋭く尋ねたダビデ王のように、現在進行形の苦しみ表現で私たちへの共鳴を引き起こし、「ダビデ王がそうしたように、あなたも苦しみを終わらせるよう神に訴えていいのだ」というメッセージを伝えている。神は「涙のパン」(詩篇80章5節)だけを与えられる、と言ったとき、預言者アサフは心の中にある何とも形容しがたい感情を表現しようと試みたのだった。

最も大事なのは、こういった人々のメッセージには「主はわたしの味方、わたしは誰を恐れよう」(詩篇118章6節)に表されるような(不安への)神学的解決方法を示していると言う事だ。詩篇が歌として奏でられることを目的とした詩であり、しかもそれが霊感を受けた神の言葉であることを思い起こせば、その慰めは格別なものになる。カルバンの表現を借りれば、困難の最中に詩篇を唱えるとき、私たちの心には神の霊の歌声が響き渡っているようなものなのだ。

もちろん、旧約聖書の言葉が不安感に抗うのに役立つとは思えないことだってあるだろう。

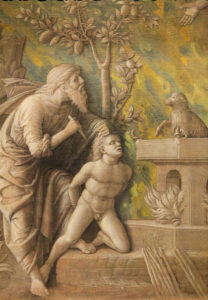

イスラエルの民に対する裁きの約束(ミカ2章3–5節)や、イサクを生贄として捧げかけたアブラハムのような厳しい試練の物語(創世記22章1‐18節)などに、打ちのめされるような時もある。

こういった物語は慰めるどころか、私たちの不安を煽るばかりだ。しかし注意深く読めば、その不安は一時的なものであって、そのメッセージの中心命題が「信仰と希望をもって神に近づくこと」であること、一つひとつの物語は神が私たちを取り返そうという試みであることが分かる。

聖書は決して、信仰者を虐(いじ)めて絶えず恐れさせたり、善い神への信仰を強制することを意図して書かれてはいない。

実存的な質問をすること

[toggle]After sharing stories and offering reassurance, Old Testament texts often issue a challenge: Will you enact the faith that you profess? It may seem trite, but it’s exactly what we need to hear if anxiety is at least partly the product of our will—a habit of mind that can be counteracted.When I was visiting a professional for strength-based counseling, this was the issue he kept discussing with me. “Isn’t your God one of infinite love and care? How does that relate to your anxiety?” It’s unsettling to have a non-Christian pressing you on the disconnect between your orthodoxy and your orthopraxy, but he was right. You can only say the Serenity Prayer for so long before the line “courage to change the things I can” becomes less of a statement and more of an imperative. [/toggle] 物語を伝えて安心感をもたらした後、旧約聖書は「あなたは自ら告白した信仰を実行しますか?」といった課題を与えてくることがしばしばある。

それは些細なことのように思えるかもしれないが、その不安が(少なくとも部分的に)私たちの意識からくるものかどうか、つまり改善できる心の習慣であるかどうかを確かめることは大事なプロセスだ。

私が「強み中心のアプローチ」の専門家の下でカウンセリングを受けていたときにも、この問題はしばしば話題に上ったのだが、彼は「あなたの神は無限の愛と優しさを与えてくれるのではないですか? そのことはあなたの不安感にどのように作用すると思いますか?」と私に繰り返し尋ねた

信仰の教理と実践に隔たりがあることをクリスチャンではない人に指摘されるのは気分の良いものではないが、彼の言う事はもっともだった。ニーバーの祈りにある「変えられるものを変えるための勇気」を繰り返し唱えていれば、その言葉は使命や命令的な意味合いを帯びるようになるはずだ。

(一部抜粋)

神よ

変えることのできるものについて、

それを変えるだけの勇気をわれらに与えたまえ。

変えることのできないものについては、

それを受けいれるだけの冷静さを与えたまえ。

そして、変えることのできるものと、変えることのできないものとを、

識別する知恵を与えたまえ。

(ラインホルド・ニーバー)

不安から変化していく信仰者と「そこ」に伴う神

[toggle]The Old Testament fits nicely into this movement from comfort to command. Joshua tells the Israelites to enter Canaan with courage (Josh. 1:18). Proverbs contrasts the wicked and the godly based on how they relate to fear and anxiety: “The wicked run away when no one is chasing them, but the godly are as bold as lions” (28:1, NLT). In Isaiah, the prophet challenges Ahaz as he worries about the threat of military invasion: “If you do not stand firm in your faith, then you will not stand at all” (7:9).Crucially, these commands are not issued from a finger-pointing God who stands back as we are thrown into the terrors of life. This God is ever present, and—even as he commands us—he is already walking with us, leading us down paths that we cannot travel on our own. This is the message of Psalm 23:4, which some translations render: “Even when I walk through a valley of deep darkness, I will not be afraid because you are with me” (ISV, emphasis added). This translation helps us to see that God walks with us, not only as we approach death but in all of the dark moments of our lives. He is always there. [/toggle]

旧約聖書には、慰めが命令に変容していくまでの動きがうまく描かれている。

ヨシュアは勇気を持ってカナンに入るようにイスラエル人たちに語る。(ヨシュア1章18節)

そして箴言は心配や不安について、悪しきものと正しい人がもつ神との関係を引き合いにして語りかける。

悪しき者は追う人もないのに逃げる、正しい人はししのように勇ましい。(箴言28章1節)

預言者イザヤは軍事侵攻の脅威におののくアハズ王にこう呼びかける。

信じなければ、あなたがたは確かにされない(イザヤ7章9節)

重要なのは、私たちが身を投げうって恐怖に立ち向かう時、その命令を下す神は高みの見物を決め込んでいるわけではない、ということだ。神は常に存在し(命令を下すときでさえ)すでに私たちと歩みを共にしているし、私たちだけでは踏み出せない一歩を導いてくれる。これこそが詩篇23章4節のメッセージなのだが、この聖句については少し趣(おもむき)の違う翻訳もある。

深い陰の谷を行くときも、あなたと共にいるわたしは恐れを抱かない。(ISV)

この翻訳では「死に近づく時だけではなく、人生における暗い旅路すべてにおいて神は私たちと共に歩んでいる」ということが強調されている。神はいつも「そこ」にいる存在なのだ。

(続く)

著者のB.G. ホワイト氏はニューヨーク市にあるキングズカレッジの助教授(聖書学)、牧師。神学者センター・フェロー。

本記事は「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(米国)より翻訳、転載しました。翻訳にあたって、多少の省略をしています。

出典URL:https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2019/november-web-only/neuroscience-and-scripture-agree-it-helps-to-lament-in-comm.html?fbclid=IwAR0wsNJdWrveRHsfALI-MTmPJ_jHNXPI1wQkcMT8OsP3sZWIgZ1qgZ8YInA