「高学歴が世俗化に関連している」という通説は間違っており、この問題により具体的に取り組む方法がある。

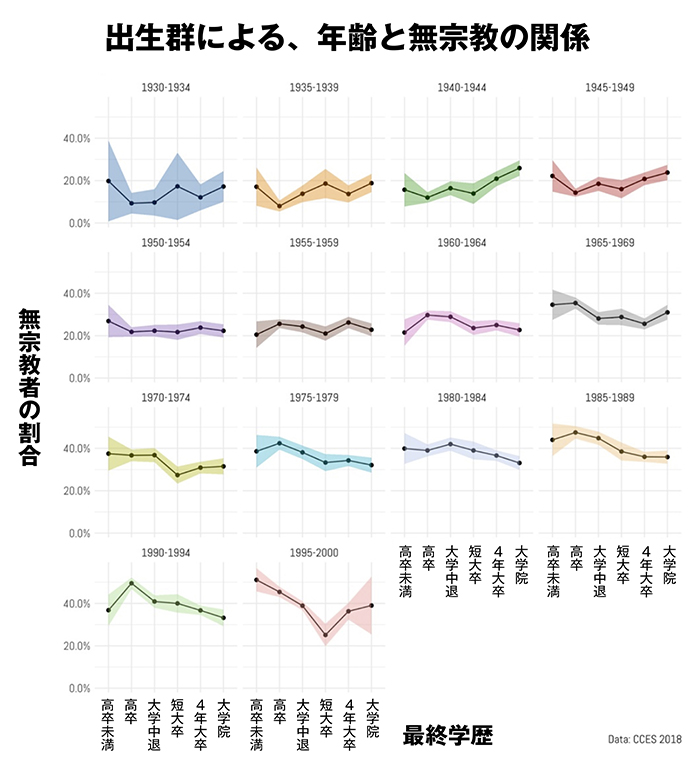

[toggle]However, there is a more specific way to approach this problem. The above graph lumps the entire sample into six education categories with little regard for whether they obtained their high school diploma in 1968 to 2008. [/toggle]「世俗化が絶えず加速している」と考えるのであれば、大学院の学位を持つ若者が年々高い割合で宗教に無関心になっていると期待されるだろう。これを実証するため、CCES調査は2018年にサンプルを出生群ごとに分割した。出生群は5年間隔で作成されている。

[toggle]If secularization was a constantly accelerating process, we would expect to see younger people with graduate degrees unaffiliate at higher rates than their older counterparts with high levels of education. In order to test this, I broke the CCES 2018 sample into birth cohorts, which are created based on five year intervals. [/toggle]たとえば、1940~44年に生まれたすべての人を同じ出生群に入れ、次に、14個のサンプルの出生群すべてについて、各教育レベルにおける無宗教者の割合を計算した。

[toggle]For instance, I placed everyone born between 1940 and 1944 into the same cohort. I then calculated the share of each educational level who had no religious affiliation for all fourteen birth cohorts in the sample. [/toggle]

このように視覚化すると、右肩上がりの線は世俗化を支持し、右肩下がりの線は、世俗化が発生していないことを示す。いちばん上の列、1930年から49年までの出生群については、高い教育を受けている人は宗教に関わっていない可能性が高く、世俗化のいくらかの傾向が見られる。

[toggle]For this visualization, an upward sloping line would provide support for secularization, while a downward sloping line would indicate that secularization is not occurring. For the top row of cohorts, ranging from 1930 to 1949, there is some evidence of secularization, as those with more education are more likely to be unaffiliated. [/toggle]しかし、2段目は明らかに違って、折れ線グラフは平らに近い。これは、1950年から69年の間に生まれた人々にとって、教育と宗教離れとの間に関係がないことを示す。最後の6つの出生群(1970年~2000年生まれの人々)は右肩下がりになっており、このグラフの結果、18歳から49歳までの人々にとって、より高い教育があるほど、宗教的伝統を守る可能性が高いことを示している。

[toggle]The second row, however, tells a different story: the lines are flat. This indicates there is no relationship between education and religious disaffiliation for those born between 1950 and 1969. The last six cohorts (those born between 1970 and 2000), show lines that consistently sloping downwards. The results of this graph indicate that, for those between the ages of 18 and 49, the more education one obtains the more likely they are to affiliate with a religious tradition. [/toggle]まとめると、このサンプルの結果から言えることは、米国の古い世代にとっては世俗化は明らかだが、1950年以降に生まれた人々には、教育が宗教的所属の衰退につながるという証拠はない。

[toggle]Taken together, the results from this sample tell a simple story: secularization is apparent for older generations of Americans, but for those born after 1950 there is no evidence that education leads to a decline in religious affiliation. [/toggle]それでは、なぜこのようなことが起こっているのだろうか。社会学者のフィリップ・シュワデル氏は、2014年に発表した論文で見解を発表した。

[toggle]So, why is this happening? The sociologist Philip Schwadel provides some insight in a paper he published in 2014. [/toggle]第一に、高等教育を受けることが現代の米国社会には広く行き渡っているという。何年も前には、特定の人々しか大学に進学しなかったが、現在では大学教育は、あらゆる社会経済的・人種的・宗教的背景の人々にとって可能となっている。それは、前の世代で起こっていた自己選択効果を弱めているのかもしれない。

[toggle]First, Schwadel notes that obtaining a higher education has become ubiquitous in modern American society. While only certain types of people would go on to college in previous years, a college education is an obtainable reality for people from all types of socio-economic, racial, and religious backgrounds. That may mute the self-selection effect that was occurring in prior generations. [/toggle]加えてシュワデル氏は、「教養がある人はしばしば、文化的変化の初期に影響を受ける」と主張している。それは、1970年代と80年代に宗教的な絶縁への移行につながった。その後、その影響は、同じように宗教から関係を断ち始めた残りの人々へも波及した。したがって、最近の出生群で起きている現象は、反対方向に揺れている振り子のように、高い教育を受けた人の一部が宗教に戻ってきていることを示す。

[toggle]In addition, Schwadel argues that the well-educated are often early adopters of cultural change, which meant a move toward religious disaffiliation in the 1970s and 80s. Subsequently, those behaviors then trickle down to the rest of the population who began to disaffiliate from religion as well. Therefore, what may be occurring in the younger cohorts is the pendulum swinging in the opposite direction, with the highly educated portion of the population returning to religion. [/toggle]「子どもたちは大丈夫」という言葉は、繰り返し使用される。「最近の若い米国人は、より高い教育を受けているために宗教的ではない」という認識は、このデータを見る限り裏づけがない。

[toggle]To use an oft-repeated phrase, “The kids are alright.” The perception that younger Americans are becoming more educated and therefore less religious finds no empirical support in this data. [/toggle]実際、より心配なのは、高校以上の教育を求めない若者かもしれない。彼らの多くは、教会出席について、あらゆる出生群における最低レベルだ。「成人の60%がどんな宗教も持っていないスウェーデンのように、米国の先行きはなるのではないか」と考える人がいるなら、それはありそうもないようだ。

[toggle]In fact, a bigger worry may be young adults who don’t pursue education beyond high school, as many of them are espousing the lowest levels of church attendance of any birth cohort. If one thinks that the path of the United States looks like Sweden, where 60% of adults have no religious affiliation, that seems unlikely. [/toggle]クリスチャン・ファミリーの子どもを世俗的な大学に送り出すとき、両親が抱くいくつかの懸念を、この結果は軽減するはずだ。若者の世代では、より高い教育を受けている者のほうが教会出席率は高く、また宗教から離れる可能性も低い。その証拠は明らかだ。米国にはまだ宗教への希望があるようだ。

[toggle]In addition, this should alleviate some of the concerns that parents have when they send their Christian teenagers off to a secular college or university. The evidence is clear: among their generation, more education leads to higher levels of church attendance and a lower likelihood of becoming religiously disaffiliated. There is hope for religion in America, yet. [/toggle]執筆者のライアン・バージ博士は、イースタン・イリノイ大学の政治科学の教授。米国のさまざまな機関や行政、そして国際関係を含むさまざまな分野について教えている。彼の研究は、特にアメリカ大陸における宗教と政治的行動との交差におもに焦点を当てている。

本記事は「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(米国)より翻訳、転載しました。翻訳にあたって、多少の省略をしています。