ある日、妻と言い争いをしていた。何の話題だったか、確かなことはとうに忘れた。言い負かされそうになったとき、私は苛立ちのあまりダイニング・ルームの壁を殴った。壁はもちろん微動だにしなかったが、穴くらいは開いたんじゃないかと思った。幸いなことに(あるいは運命的に)、私が力いっぱい殴った壁は、柱で支えられていた箇所だった。控えめに言って、かなり痛かった。

[toggle]One day my wife and I were arguing about something—the exact subject has long been forgotten. In the course of the argument—probably when she was getting the best of me—I became so frustrated that I hit our dining room wall with my fist. The wall didn’t move, of course, but I expected to at least put a hole in the drywall. As fortune (or providence) would have it, the place I decided to punch with all my force was backed by a two-by-four stud. Let’s just say it hurt. [/toggle]そのあと私たちは黙り込み、キッチンとダイニングの掃除を始めた(当時はリフォーム中だった)。手が異常なことはすぐに分かった。私は右手でほうきを握ることすら、ほとんどできなかったのだ。

[toggle]We both fell silent after that, and I set about sweeping up the kitchen and dining room (we were remodeling at the time). It became immediately apparent that there was something wrong with my hand, as I could barely hold on to the broom with my right hand. [/toggle]妻は、私が痛がり、手も異常であることに気がついた。手をそっと持ち上げ、観察したあと、「骨が折れてるんじゃないかな。緊急外来に行こう」と言った。彼女の予想は、やがて診療所の医療スタッフの同意を得ることとなる。

[toggle]My wife noticed that I was in pain and that my hand didn’t look right. She gently lifted my hand to look at it. “I think it’s broken,” she said. “We need to get you to the emergency room.” Her diagnosis was soon confirmed by the medical staff at the clinic. [/toggle]私の手を見た時から、彼女から怒りや憤り、優越感は消えていた。そういった感情を持つ正当性があったにもかかわらず、彼女はただただ私のことを心配していた。壁を殴ったとき、私が彼女に攻撃的だったことはよく分かっていた。しかし、彼女が目を留めたのは、自分ではなく他の場所に怒りをぶつけたこと、そして私が自らの愚かさで痛い目に遭ったことだった。

[toggle]From the point where she looked at my hand, there was no anger, resentment, or moral superiority on her part—all of which would have been justified. She was just concerned about my welfare. She very well knew that there was some part of me that was striking out at her when I hit the wall, but instead she focused on the fact that I vented my anger elsewhere than at her and was in deep pain as a result of my foolishness. [/toggle]

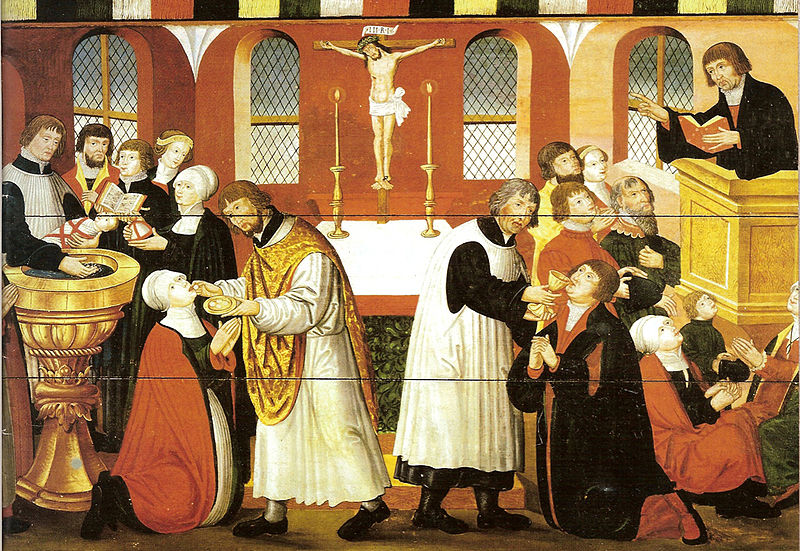

トアスロネ教会で説教するマルティン・ルター(1561年)

私はこの例話を、恵みについての説教に使った。たとえ私たちが敵対的で、神自身にそれをぶつける時でさえ、神は思いやりと慈しみをもって私たちを扱ってくださるという真実を伝えようとしたのだ。私はそれを完璧な具体例だと思った。

[toggle]I used this illustration in a sermon on grace. It was the final illustration, tailored to drive home the truth that God treats us with kindness and grace even when we show ourselves to be hostile and angry, even toward him. I thought it the perfect illustration. [/toggle]結果的に、そのメッセージを聞いたほとんどの人は私の意図を理解してはくれなかった。礼拝直後や、そのあと数週間の間に受け取った感想には3種類あった。

[toggle]Turns out, very few listeners heard all that. Comments after the service, and for a few weeks running, were of three sorts: [/toggle]ある人は、「自分の弱さをさらけ出して話してくださってありがとう」と語りかけ、周りの人に聞こえないよう声のトーンを下げてから、「私にも同じ経験があるけど、他の人に話すのが怖すぎて」と言った。もちろん、「すごく面白かった!」といった反応もあった。しかし、そのエピソードを聞いて、「神の恵みをより深く理解できた」と言う人はいなかった。ただの一人も。

[toggle] “Thank you for being so vulnerable and sharing that story.”And, in a low voice so no one else could hear, “I’ve done that but was too afraid to tell anyone.”

And of course, “That was so funny!”

No one ever told me that as a result of the illustration they understood God’s grace better. No one. [/toggle]

彼らが得たのは、私についての理解だった。私の気質と、私が自分の何を変えようと努力しているか、私の妻のこと、そして私の結婚生活について知り、その話を楽しんだのだ。

[toggle]But they understood me better. They learned something about my temper. My remodeling efforts. About my wife and my marriage. And they were entertained. [/toggle]現代の価値基準では、それは成功だったと言えるだろう。魅力的な笑い話だったし、この話を何週間も、あるいは何年も覚えている教会員さえいた。

[toggle]By contemporary standards, it was effective: It was riveting; it was funny; listeners remembered it for weeks, even years. [/toggle]しかし、彼らは間違ったことを覚えてしまったのだ。彼らが心にとどめたのは私のことだった。私から見る限り、神の恵みについて彼らが気づいたことは何一つなかった。これは、これまでに使った例話の中でも最低のものだと私は結論づけた。

[toggle]But they remembered the wrong thing. They remembered me. They didn’t remember anything about God’s grace, as far as I could tell. Therefore I have concluded that it was about the worst illustration I ever used. [/toggle]問題は、このような例話を説教で紹介することが伝道の常識となっていることだ。それは、いま伝道が悲惨な状況にある理由の一つでもある。

[toggle]The problem is this: This type of sermon illustration is the order of the day in evangelical preaching. And it’s one reason evangelical preaching is in dire straits. [/toggle]形式が実体になるとき

[toggle]When Style Becomes Substance[/toggle]説教は、人間関係以外の事柄について聞くことができる週に一度の機会だ。それは神について、神の愛の奇跡と神秘について、そして神が私たちのためにキリストにおいてなさったことについて聞く時だ。しかし説教は、私たちのことを話すこと、あるいは説教者自身について知るための方法になってしまった。

[toggle]Preaching is one time in the week when we have the opportunity to hear about something other than ourselves, other than the horizontal. It’s the time to hear about God and the wonder and mysteries of his love, of what he’s done for us in Christ. But more and more, evangelical preaching has become another way we talk about ourselves, and in this case, to learn about the preacher. [/toggle]世の文化との融和を図るため、多くの教会はまたもエンターテインメントの世界をモデルにした。多くの福音派教会の説教は、スタンドアップ・コメディーと深夜番組の冒頭トークの中間のようなものになってしまった。重要とされているのは、それが「自分を見せる」ものだということだ。その説教は自然体で、原稿を読み上げるわけでもなく、おまけに笑える話だ。

[toggle]Once again, in the interests of identifying with the culture, the entertainment world has become the model here for many churches. To begin with, the sermon in many evangelical churches represents a cross between the patter of a standup comic and the opening monologues of late-night television. The idea is to be “authentic”—that is, natural and unscripted and funny to boot. [/toggle]もちろん、これは恐ろしく世間知らずな見方だ。コメディーのパフォーマンスは、ほとんどが原稿化されている。コメディアンの動きやキャラ設定は、何カ月、あるいは何年にもわたる練習によって磨き上げられたものだ。深夜番組のコメディーは間違いなく楽しいものだが、その娯楽性は「自分を見せる」ことから来るものではまったくない。彼らはプロとして深い研鑽(けんさん)を積んでいるのだ。

[toggle]This, of course, is naive as naive can get, because you can be sure that those opening monologues are hardly unscripted. The patter of the comedian, as well as his or her persona, has been fashioned and sharpened with months or years of practice. Late-night TV hosts and comics are entertaining, no question about that. But they are entertaining precisely because they are anything but authentic. Instead, they are deeply practiced in their profession. [/toggle]説教は、テレ・プロンプター(原稿を映し出す装置)を使うか、何カ月も同じギャグを繰り返し練習することなく、その真似をしようとしている。舞台上での練習もせず、メモや説教原稿すら用意していない。説教者は自分のオフィスで静かに練習し、決めぜりふを覚えて、どういうタイミングで、どういう仕草を入れるかを考える。そうして自分を見せる演技をしているのだ。

[toggle]The evangelical sermon mimics all this but without the use of a teleprompter or without repeating the same shtick honed over months of gigs. There are no podiums or pulpits, no notes, not to mention a sermon manuscript. You can be sure, however, that the preacher has practiced the sermon in the quiet of his or her office and memorized his or her best lines, as well as the right gestures at the right moment—all so that he or she can appear authentic. [/toggle]問題なのは、そのような状況だけでなく、話の内容自体だ。説教は結局のところ、人間関係のことについて終始してしまっている。説教の長さや形式という枠組みの中で、話す者の人生経験や例話に基づいたメッセージは結局、思いとは裏腹に、説教する者に焦点が当てられてしまう。

[toggle]It’s not just the setting but the content that communicates the most troublesome thing: that the sermon is, in the end, mostly about the horizontal. Given the length of the sermon and the method of delivery and the personal illustrations from the preacher’s life to drive home the message—it all brings an inadvertent focus on the one who is preaching. [/toggle]ここで強調したいのは「思いとは裏腹に」ということだ。多くの説教者がこうした現代的な説教スタイルを用いるのは、自らを誇ろうとしているからではないと私は思っている。彼ら彼女らも神を愛し、神のことを告げ知らせようと努力している。ただ、そのスタイルでは、自らが目指している目的を達成できないことに気づいていないのだ。(中編に続く)

[toggle]Let me emphasize that word inadvertent. Because I doubt if many preachers invest in this style of contemporary preaching so as to exalt themselves. These men and women love God and strive to make him known. What they don’t recognize is that the style they are engaged in thwarts their desires. [/toggle]