(前編を読む)

この古代ギリシア語の聖書翻訳から二つの特徴が初めて発見されたが、それは現代英語聖書と驚くほど対応している。

[toggle]Two characteristics found for the first time in this ancient Greek translation correspond in remarkable ways to our modern English Bibles. [/toggle]

70人訳聖書

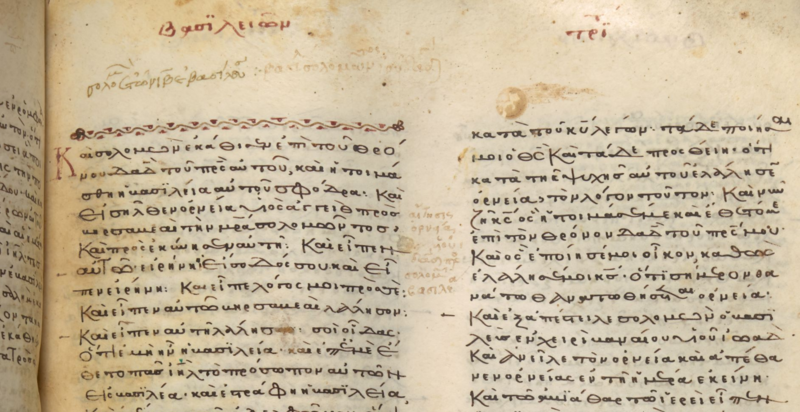

まず、新しく発見された断片には、神の名前の4文字である「テトラグラマトン」に対する特別な扱いが示されている(テトラグラマトンとは、ギリシア語で「四つの文字」という意味。ヘブライ語で「神様」は「ヤーヴェ」「ヤハウェ」というが、その御名を口にすることは禁じられているので、いろいろな言い回しがあり、その一つが「テトラグラマトン」だ。「ヤーウェ」の「アレフ、ヘ、ヴォヴ、ヘ」のこと。出エジプト3:14~15参照)。ギリシア語「キュリオス」(主)という典型的な方法で名前を表現する代わりに、神の名前は右から左に書かれたヘブライ文字で表されている。これは、英語の文章の途中でヘブライ語の文字「יהוה(YHWH)」やラテン語の「DOMINUS(主)」を使用するのと似ている。

[toggle]First, the newly discovered pieces show a special treatment for the four letters of God’s name, the Tetragrammaton (see Exodus 3:14–15). Instead of rendering the name in typical fashion with the Greek word Kyrios, the name of God is represented in Hebrew letters written right to left. It would be similar to us using the Hebrew letters יהוה (YHWH) or possibly the Latin DOMINUS in the middle of an English sentence. [/toggle]神の名前に特殊な文字を使用することは現代聖書にも引き継がれているので、この表現は重要だ。多くの学者が示唆しているように、ほとんどの英語聖書ではその名前を、想定される発音の「ヤハウェ」ではなく、大文字で「the LORD(主)」としている。この置き換えは、その音によって神の名前を表す代わりに、ヘブライ語の「主」である「アドナイ」、あるいは「名前」である「ハシェム」と読む古代の伝統に従っている

[toggle]This representation is significant because using specialized characters for the divine name has carried through to our modern Bibles. Most English Bibles represent the name as “the LORD” with small capital letters, rather than representing its supposed pronunciation Yahweh, as many scholars suggest. This substitution follows the ancient tradition of reading Adonai, a Hebrew word meaning “Lord,” or even HaShem “The Name,” in place of representing God’s name according to its sound. [/toggle]さらに、この神の名前の書き方は、他のほとんどの「死海文書」におけるヘブライ語写本と一致しない。これはさらに古いもので、「古ヘブライ文字」と呼ばれることもあり、第二神殿時代には日常の執筆でほとんど使われなくなったものだ。現代のラテン文字と亀甲文字かゴシック文字の違い、あるいはギリシア文字のようなものと考えてほしい。こうした表現を翻訳文に入れることで、執筆に対する異質性と、名前の独自性に対する敬意の一種という両方が込められている。

[toggle]Moreover, the lettering for God’s name is not typical of most of the other Dead Sea Scroll Hebrew manuscripts. It is an even older script, sometimes called paleo-Hebrew, which was mostly abandoned in everyday writing during the second temple period. Think of it as the difference between our modern Latin lettering and the calligraphic Fraktur or Gothic script, or possibly even like Greek letters. Putting these representations into a translated text provides both a foreignness to the writing and a type of reverence for the name’s uniqueness. [/toggle]新しい断片で見つかった2番目の相関関係は、新しい翻訳を改善しようとするために単語を変更したという証拠だ。この小預言書の巻物は、ヘブライ語聖書の古いギリシア語訳の改訂版を表している。元のバージョンは、1世紀にギリシア語を話すユダヤ人によって地中海世界全体で広く使用されていたが、ある時点で新しい翻訳が必要になった。

[toggle]The second correlation we find in the new fragments is evidence of changing words to try to improve a new translation. The Minor Prophets scroll represents a revision of an older Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. The original version was used widely by Greek-speaking Jews in the first century throughout the Mediterranean world, but at some point, a new translation became warranted. [/toggle]ゼカリヤ書8章17節の場合、70人訳では、ヘブライ語のテキストにおける最初の単語(אִישׁ)を、あらゆる主要な英語聖書と同じように、「互い、別の」を意味する副詞として最後に置いた。たとえばNIVでは、「互いに悪をたくらむな」と訳されている。

[toggle]For Zechariah 8:17, the Old Greek translated the first word in the Hebrew text (אִישׁ) as a distributive term meaning “each other, another,” which put at the end, similar to every major English version. For example, the NIV reads, “Do not plot evil against each other.” [/toggle]一方、新しい断片では、同じ用語が最初に別のギリシア語で翻訳されている。行間に翻訳を記していくアプローチで、それが使われた文脈を考慮せずに対応する単語を見つけると、この節は、「人」と同じヘブライ語を表すことから始まる。それではあまりに文字どおりの翻訳となる。「人に関しては、心の中で隣人に対して悪をたくらんではならない」

[toggle]In the new fragment, the same term is translated by a different Greek word at the beginning. Using an interlinear approach—finding a corresponding word without accounting for the context of its use—the verse starts by representing the same Hebrew word as “man.” It forms an overliteral translation: “As for a man, do not plot evil against his neighbor in your heart.” [/toggle]聖書を正確に共通言語へと翻訳しようとする努力は、聖書の最初期のテキストによる証拠にまでさかのぼると思われる。しかしこの違いから、私たちの言葉で神の言葉を表現する最善の方法ついてのさまざまな現代的な意見が出てくるだろう。

[toggle]It would seem that the efforts to render the Bible accurately into common languages date back to our earliest textual evidence of the Scriptures. Yet this difference anticipates the various modern opinions about how best to represent God’s word in our vernaculars. [/toggle]これらのテキストによって、今後間違いなく数年間で多くの研究が開始され、その他の特性もマルチ・スペクトル画像とデジタル拡大によって明らかになる可能性がある。聖書学者として私は、古代の読者がヘブライ語聖書を翻訳しようと努力する姿を想像できる。そのヘブライ語聖書は、私たちが今日読んでおり、これらの意味あるテキストを古代の人々の歴史における最も暗い瞬間へと導き、神と彼らの世界とをよりよく理解するのを助けるものだ。

[toggle]These texts will undoubtably launch an array of research in years to come, with other features possibly revealed through multispectral imaging and digital magnification. As a biblical scholar, I can imagine these ancient readers striving to translate the Hebrew Scriptures that we read today and then carrying these meaningful texts into the darkest moments of their history to help them better understand God and their world. [/toggle]この古代のテキストを通じた彼らとのつながりは、今では少しずつ小さな断片で提示されており、特に「最も大きな試練と不確実性の瞬間に神を求めたい」という人間の深い願望を示している。

[toggle]Our connection to these people through this ancient text—now brought forward in tiny pieces, bit by bit—demonstrates the profound human desire to seek God especially in our moments of greatest trial and uncertainty. [/toggle]執筆者のチップ・ハーディは、サウス・イースタン・バプテスト神学校の旧約聖書とセム語の准教授で、『聖書ヘブライ語からの聖書釈義の宝石──文法と解釈へのリフレッシュ・ガイド』の著者。

[toggle]Chip Hardy is associate professor of Old Testament and Semitic Languages at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and the author of Exegetical Gems from Biblical Hebrew: A Refreshing Guide to Grammar and Interpretation.[/toggle]本記事は「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(米国)より翻訳、転載しました。翻訳にあたって、多少の省略をしています。