(1を読む)

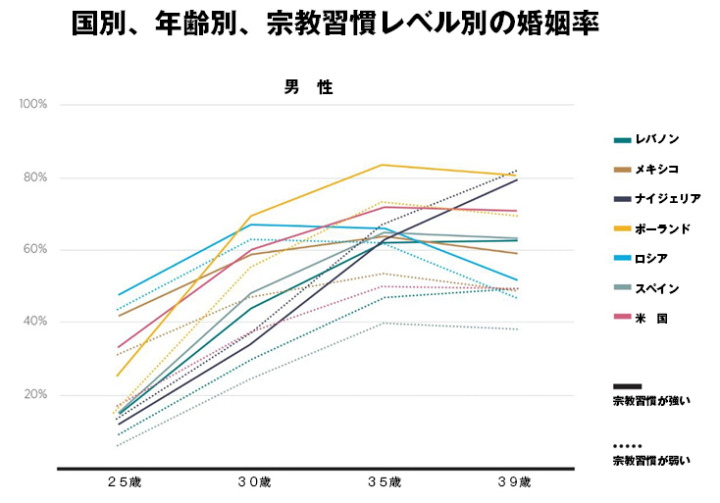

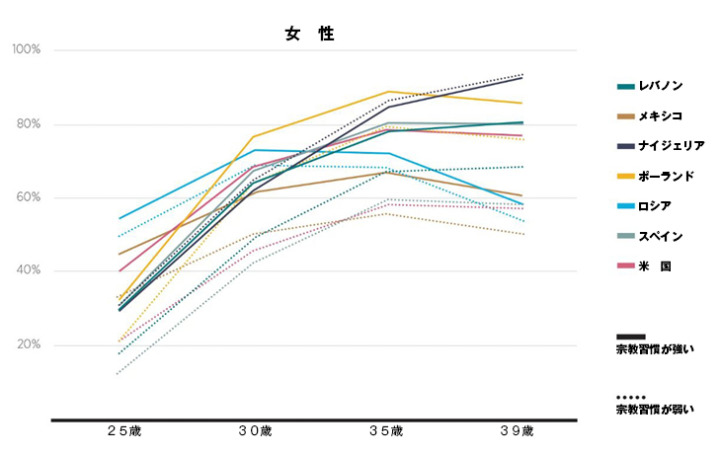

前回紹介した、結婚に不安を持つアンデルのケースは、結婚志向が低下しているクリスチャン男性の一つのケースだ。下に示す世界価値調査のデータによると、私が調査した7つの国で日常的に礼拝に出席する人は、年齢層を問わず、結婚について好意的だという。しかし、将来どうなるかの予測については、国によって異なる結果が出た。

[toggle]Ander is only one of many Christian men who are part of the downward turn in marriage trends. According to data from the World Values Survey, regular church attenders in the seven countries I studied do indeed have a better shot at being married—at almost every age. But the predictions varied across countries. [/toggle]

たとえば、毎週教会に通うポーランド人女性のうち、30歳までに結婚すると予想されるのは76%、35歳までは88%だ。これは米国とスペインの同年齢の数字より10%ほど高い。

[toggle]For example, 76 percent of Polish women who attend church weekly are expected to be married by age 30, and 88 percent by age 35. That’s about 10 percentage points above women of the same age in the United States and Spain. [/toggle]教会に通う人とそうでない人との結婚観には顕著なギャップがある。米国では、35歳までに結婚すると予想されているのは、毎週教会に通う男性だと72%だが、教会に通っていない男性は50%に留まっている。

[toggle]The marriage gap between churchgoers and everyone else, however, is especially striking. In the United States, 72 percent of men who attend church weekly are expected to be married at age 35, while the same is predicted for only 50 percent of American men who don’t regularly attend. [/toggle]

米国の福音派の状況はどうだろうか。オースティン・インスティテュートが収集した全国調査では、20歳から39歳までの福音派クリスチャンのうち56%が現在結婚している。これは、福音派クリスチャン以外の同年代の人を含めた数字(42%)を大きく上回っている。しかし4年後の再調査では、それは明らかに低下していた。2018年後半、福音派クリスチャンの20歳から39歳で結婚していたのは51%だが、全人口の同年齢帯の婚姻率は40%だった。比較的まだ多いとはいえ、福音派クリスチャンのほうがその低下スピードが速い。

[toggle]How do American evangelicals fare? In a nationally representative survey collected in 2014 for the Austin Institute (where I’m a research fellow), 56 percent of self-identified evangelicals between ages 20 and 39 told us they were currently married. That number is well above the 42 percent reported by the rest of the same-age population. A repeated inquiry four years later yielded an obvious dip. In late 2018, 51 percent of evangelicals 20 to 39 were married, compared to 40 percent of that total population. The number is still higher, but it’s falling faster. [/toggle]一方、「パートナーと同棲している」と答えた福音派クリスチャンの割合は、同期間で比較すると、3・9%から6・7%に上昇している。また、同棲について肯定的に捉える意見は、2014年の16%から18年後半には27%まで増加した。調査に応じた福音派クリスチャンのほとんどは「結婚は時代遅れ」とは思っていないが、少数派が増えていることを考えれば、そのような考えが今後広まることもあるだろう。

[toggle]Meanwhile, the portion of evangelicals who said they were cohabiting rose from 3.9 percent to 6.7 percent in the same span of time. Support for cohabitation sprouted from 16 percent of this population in 2014 to 27 percent by late 2018. Very few of the surveyed evangelicals believe that marriage is “outdated,” but a growing minority of them now perceive an alternative pathway to get there. [/toggle]この顕著な低下傾向は、教会側の調査でも見られる。カトリックの「教会年鑑」を見ると、1965年のカトリック教会(米国)と比べ、現代の婚姻率は59%低下している。65年の葬式と結婚式の比率は10対9だったのに対し、2017年までにその数字は10対3・7まで減っている。40歳未満をおもなターゲットとする現代的な福音派教会を除けば、ほとんどの教会が結婚より埋葬の儀式を執り行うほうが多い。

[toggle]Official church records also note obvious decline over time. A look at the Statistical Yearbook of the Church, a Catholic publication, reveals that Catholic marriages in the United States have plunged 59 percent since 1965, when there were 9 weddings for every 10 funerals. By 2017, that ratio had dipped to 3.7 for every 10. Unless you’re pastoring a hipster evangelical church whose median age is under 40, you may be doing more burying than marrying. [/toggle]それはなぜだろう。疫病による不安が広がっていることが要因の一つであることを、前回のアンデルや類似例のケースは示している。

[toggle]Why? One understated factor is the endemic uncertainty exhibited by Ander and others like him. [/toggle]理論的には、約束を取り交わすことによって、そうした不安は軽減されるはずだ。それが財政面での約束であれば、なおさらだろう。一人で取り組むよりも二人で取り組んだほうが、より多くのことが達成できるからだ(「一人より二人のほうが幸せだ。共に労苦すれば、彼らには幸せな報いがある。……」コヘレト4:9~12)。

しかし、ほとんどの男性と女性は、そのようには結婚のことを認識しなくなった。私が調査を行ったどの国でも、「結婚は、物質的・社会的・心理的な不安の緩和や解消に一貫して有効だ」という話を聞くことはなかった。

[toggle]In theory, committing should diminish such doubt—especially if it concerns finances. After all, two together can accomplish more than one (Ecc. 4:9–12). But most men and women don’t perceive marriage this way anymore. In no country did I hear a consistent description of marriage as a means to combat or mitigate material, social, or psychological uncertainty. [/toggle]むしろ現実には、その正反対の話を聞くことが多い。正教会のクリスチャンであるビクトール(モスクワ、29歳)もその一人だ。

彼は妻や子どもを持つことに関心がある一方で、結婚に対する不安も抱いている。妻が情緒不安定になったり難しい状況に置かれたりしたら、自分はどうすればいいのだろう。もし家族を養うのに苦労したとしたら。小さなアパートに住むことによる苦労もある。彼は言った。「現代の大都市のような環境で家族を作ることはとても難しい」

[toggle]In fact, I heard quite the opposite from many of my interview subjects, including Victor, a 29-year-old Orthodox Christian in Moscow. The very concept that he’s attracted to—having a wife and children—creates questions in his mind. What would he do if his wife became unstable or difficult? What if he struggled to support his family? And what about the challenge of living in a tiny apartment? “It’s very problematic,” he told me, “to create a family in the conditions of a modern metropolis.” [/toggle]この「大いなる不安」というパンデミック(世界的大流行)は、性理解の変化や働き方改革(フリーランス)、低所得の男性の増加といった単純な要因で理解できる話ではない。理解すべきなのは、結婚がもたらすものは変化していないにもかかわらず、人々が持つ結婚への期待が大きく変化しているということだ。

[toggle]The story of how this pandemic of uncertainty came to be is no straightforward tale about sexual revolutions, gig economies, or substandard men. Instead, what people expect from marriage has changed profoundly, even though what marriage offers has not. [/toggle]

(写真:Dezidor)

クリスチャンでさえ結婚のことを、「成人として歩むための土台」ではなく、「成人としての成功を示す集大成」と認識している。この呼び方自体にその認識が現れている。「集大成」とは、物事をなす時の仕上げであり、瞬間的に起こるものだ。しかし「土台」とは、その上に何かを建てるためのものであり、長持ちさせる必要がある。

結婚を「土台」として認識する人々にとって、「新婚」で「貧しい」ことは普通のことで、当然予想されることであり、最初はたいへんでも、やがてそれは解消されるものだ。しかし、結婚を「集大成」として認識する人々にとっては、お金がないということは、まだ結婚の準備ができていないことなのだ。

[toggle]Marriage, even in the minds of most Christians, is now perceived as a capstone that marks a successful young adult life, not the foundational hallmark of entry into adulthood. The nomenclature attests to this. A capstone is the finishing touch of a structure. It’s a moment in time. A foundation, however, is what a building rests upon. It is necessarily hard-wearing. In the foundational vision, being newly married and poor was common, expected, and difficult, but often temporary. In the capstone standard, being poor is a sign that you’re just not marriage material yet. [/toggle]『嵐に包まれた家族』でラッセル・ムーアが嘆いたように、人々にとって結婚とは「自己犠牲の場所」というより「自己実現の手段」になってきている。

[toggle]As Russell Moore laments in The Storm-Tossed Family, marriage is increasingly a “vehicle of self-actualization” rather than a setting for self-sacrifice. [/toggle]クロエ(ミシガン州、27歳)はインタビューの中でその考え方をこう説明した。「人々にとって20代は『自分だけの時間』なんです。ほかの人を助けるのは、その後のこと」。同年代の友人にもそんな考えを持つ人が多いが、それは結婚の心構えとしては不適切だ。自己犠牲とは行動を通して学ぶものであり、30歳の誕生日にプレゼントとして贈呈されるようなものではない。

[toggle]Chloe, a 27-year-old interview subject from Michigan, explains this mentality. “You have your 20s to focus on you,” she said, “and then [after that] you try to help others.” This approach, common amongh her peers, is poor preparation for marriage. Self-sacrifice is learned behavior, not a gift for your 30th birthday. [/toggle]結婚へのビジョンが不透明なのは、裕福な西欧諸国だけではない。ペンテコステ派の信徒であるンディディ(ナイジェリアのラゴス、28歳・未婚)は、結婚の条件について明確な意見を持っていた。彼女は言う。「ほしいものがすべて揃ったら結婚します。自分で達成したいすべてのことが達成できた時に」

[toggle]Marital mission creep is not exclusive to the prosperous West, either. Ndidi, a 28-year-old unmarried Pentecostal from Lagos, was clear about the conditions under which she would marry. “When I have everything I want,” she said. “When I am able to achieve everything I want to achieve for myself. Then I will get married.” [/toggle]同じラゴス出身の別の女性(24歳・未婚)も同じ意見だ。彼女は笑って言った。「ありえないですよ! 結婚してまで苦しみたくはないです」

[toggle]Another 24-year-old unmarried woman from Lagos concurred. “Oh, please!” she said, laughing. “I can’t marry and suffer.” [/toggle]私たちが話を聞いた若いクリスチャンのほとんどは、「結婚に対して高い期待」を持ちながらも、「そのために払わなくてはいけない犠牲を面倒に思う」と明確に語った。率直に言って、若者たちは「自分の生活をあきらめたくない」のだ。ソウルメイトについての話にはうんざりしながらも、心の奥底では自分のソウルメイトを求めてもいる。

[toggle]Most of the young Christians we interviewed articulated high expectations for matrimony and a low tolerance for sacrifice. They frankly didn’t like to give of themselves too much. They might have balked at talk of soulmates, but they secretly pined for one. [/toggle]一方、そんな高い期待を持つのをやめることができたカップルは、自分たちの未来を明確に見ている。

[toggle]By contrast, couples who managed to thwart such elevated standards could see the future more clearly. [/toggle]ポーランドのクラクフに住むパーウェ(24歳)とマルタ(29歳)は、最近結婚したばかりのカップルだ。マルタは1歳の娘を育てながらフルタイムで働き、パーウェは大学院で哲学を学んでいる。

[toggle]Pawe, 24, and Marta, 29, are a recently married couple living in Krakow. Marta is a full-time mother to their one-year-old daughter, while Pawe is in the middle of graduate studies in philosophy at a nearby university. [/toggle]二人はいくつかの逆境に直面した。控えめな結婚式をしたことでお金は節約できたが、それは二人の社会的なつながりを失うことにもなった。マルタの地元である小さな町では、結婚式が非常に重要視されているからだ。パーウェは言う。「私たちが控えめな結婚式をしたことは、ちょっとした騒ぎになりました」。しかし二人には、「友人や近所の人たちを満足させること」よりもはるかに多くの価値が結婚にはあるという確信があった。

[toggle]The Krakow couple went against the current in a number of ways. By having a modest wedding, the two saved money, but in doing so, they frayed social ties. Marta is from a small town where weddings are a very big deal. “It was a bit of a scandal,” Pawe confessed, “because we didn’t have a big reception.” But she and Pawe were convinced that there’s far more to the good of marriage than satisfying friends and neighbors. [/toggle]「結婚に関する価値観が変わったと思うか」と尋ねると、マルタは即答した。「ええ、20~30年前と比べて現代の人たちは、結婚生活に快適さを求めるようになったと思います。私の親類や両親は、結婚した時にお金持ちでも家があったわけでもなかったので」

[toggle]When I asked them whether they thought marriage had changed, Marta was blunt. “Yes. It’s now about comfort in marriage, looking for comfort, [more] than it was 20 to 30 years ago,” she said. “When I think about my family and parents, they didn’t have [much] money or [own] a home.” [/toggle]二人もまた、結婚を「集大成」ではなく「土台」として捉えてきた。共に暮らす生活は決して楽なものではないものの、そこには創造主への信頼がある。それは、二人の多くの友人たちにはないものだ。

[toggle]She and Pawe have followed in that same tradition and taken a foundation view of marriage rather than a capstone one. Their life together, while hardly simple, reflects a confidence in their Maker that eludes many of their peers. [/toggle]この(結婚を「集大成」ではなく「土台」として捉える)アプローチは実用的かつ基本的なものだが、私の調査では、そのような見方をするカップルは少なかった。この調査結果を見ながら私は考えた。結婚が一般的だった過去は過ぎ去ろうとしており、世界の大多数が結婚から恩恵を受ける時代は終焉(しゅうえん)を迎えているのではないか。

今後、結婚は、「一部のエリート」が「自発的」に「消費者的発想」の中で「人生の後半」に行うものへと急激に変化するだろう。社会的強者は結婚を通して富と収入を統合し、社会的弱者は互いに助け合うこともなくなる。そのような中で「結婚と社会正義」の関係性について考える者はどれくらいいるだろうか。いや、ほとんどいないだろう。(3に続く)

[toggle]In my research, I saw very few couples esteeming this more functional, foundational, natural-next-step approach to matrimony. Here’s what that tells me: Marriage is moving away from its populist roots and is no longer a practice that most of the world’s adults participate in and benefit from. Instead, it’s fast becoming an elite, voluntary, and consumption-oriented arrangement that takes place later in life. The advantaged now consolidate their wealth and income by marrying, while the disadvantaged are left without even the help of each other. But how many of us see clearly that marriage is about social justice? Not very many. [/toggle]