距離を取りながらの関係性

[toggle]Hospitality Among Social Distancing[/toggle]歴史家ゲイリー・ファーングレンは著書『初期キリスト教の医学とヘルスケア』の中で、「紀元312年に天然痘(てんねんとう)に似た疫病が流行したとき、病人を手当てしたのはクリスチャンだけだった」と指摘している。当時の教会は、道端で死んだ人を埋葬するために墓掘り人を雇いさえした。

[toggle]Historian Gary Ferngren points out in Medicine and Health Care in Early Christianity that the only care for the sick during a smallpox-like epidemic in 312 AD was provided by Christians. The church even hired grave diggers to bury those who died in the streets. [/toggle]抗ウイルス薬や防護服が手に入る現代にあって、他人に伝染する病気の怖さを私たちはすっかり忘れてしまっていた。1350年のペストや1918年のスペイン風邪は、感染したら死ぬ可能性が高い疫病だった。「もし眠りの中に死ぬのならば、主が私の魂を受け取ってくださいますように」と人々が唱えたのは、寝る前のお決まりのフレーズではなく、真剣な祈りだったのだ。

[toggle]Something we have quickly forgotten, in the age of antivirals and personal protective gear, is the sheer fear that the possibility of sickness like this would instill in others. If you interacted with someone with plague in 1350, or with Spanish flu in 1918, there was a real possibility you would get it and die. The prayer “and if I die before I wake, I beg the Lord my soul to take” was a real plea, not a nighttime trope. [/toggle]新型コロナ・ウイルスは、私たちの日常にその恐怖を持ち込んだ。その恐怖によって人々はマスクや除菌のための商品に群がり、さらには新型コロナ・ウイルスが発生した中国と関わりがありそうな外観の人々への外国人恐怖症やヘイトクライムにさえ駆り立てられた。私たちの感覚は明らかに異常な混乱をきたしている。

[toggle]The new coronavirus has brought a bit of that fear back into our daily lives. It is a fear that manifests in shelves swept clean of masks and cleaning supplies in department stores and hospitals and even xenophobia and hate crimes against individuals for their perceived ethnicity relative to COVID-19’s origin in China. It is evident in our inboxes filling with cancellations and ever-updating protocols. [/toggle]しかし、奉仕(ホスピタリティー)の精神でマイノリティーをケアし、疫病に感染している可能性のある人々に関わることは、クリスチャンにとって中心的な使命の一つだ。その使命は、目に見えるかたち、目に見えないかたちでキリスト教の伝統と現代医学を支えてきた。病人を無条件に治療するということがなかった過去の歴史を多くの人は忘れている。

遺伝学の祖メンデル(後列右端)は修道院長だった。

事実、「ホスピタリティー」(ホスピタル=病院の語源)という言葉は、「ホスト」「ゲスト」を意味するラテン語の「ホスピス」に由来している。中世の修道院にいたカトリックの修道女や修道士が、寝床と栄養を必要とする旅人を受け入れたことから病院は始まった。この制度の中心にあった信念は、「苦しむ旅人に仕えることは、キリストご自身に仕えること」というものだ(「あなたがたは、私が飢えていたときに食べさせ、喉が渇いていたときに飲ませ、よそ者であったときに宿を貸し、裸のときに着せ、病気のときに世話をし、牢にいたときに訪ねてくれたからだ」マタイ25:35~36)。そして、「教会」を言い表すお決まりの呼び名であった「罪人のための病院」という言葉は、新たな深みを持つこととなる。

[toggle]But Christians are a people for whom hospitality toward the minority and the potentially infected is a central virtue—one that undergirds Christian tradition and the practice of modern medicine, whether we know it or not. We forget there was a time in which people did not unconditionally take care of the sick simply because they were sick. Indeed, the word hospitality (from which we get hospital), comes from the Latin hospes meaning “host” or “guest.” The first prototype of the hospital arose from medieval monasteries in which Catholic nuns or monks housed strangers in need of lodging and nourishment. These medieval institutions were centered around the conviction that to serve the suffering stranger was to serve Christ himself. That cliché metaphor for the church—“a hospital for sinners”—enjoyed a new depth. [/toggle]最近になって家庭でも使われるようになった「社会的距離」(ウイルスの感染を防ぐために対人接触を避けること)について、クリスチャンはどう対応すべきか戸惑っている。キリスト教において私たちは、交わりの伝統、そして疎外された者へのいつくしみを大事にしてきた。「支えを必要とする人々を意識的に避ける」という発想に対して引っかかりを覚えるのは自然なことだ。

[toggle]It for this reason that the now household term “social distancing”—the conscious effort to reduce interpersonal contact in order to prevent viral transmission—has Christians wondering what to do. Amid Christianity’s longstanding tradition of communion and attention to the outcast, we should expect discomfort with the idea of intentionally avoiding those in need. [/toggle]防疫対策は確かに不安をもたらすものだが、病人を隔離すること自体、昔から当然のように行われてきた。実際に私たちは今でも、死の淵にある人を病院に隔離しているし、多くの場合、それは恒久的に老人ホームに置き換えられている。私たちは孤独が蔓延(まんえん)する時代を生きており、そのことで健康への悪影響がもたらされていることもある。

「命を脅かすような病気が発生したので、何をすればいいか分からない」と、今さら驚くのはおかしな話だ。なにせ日常の中でその練習を行っていないのだ。子どもに対してそのような教育を施してきたわけでもない。私たちの文化は、死や肉体的な苦しみについて「いずれ訪れるもの」として扱うのではなく、「めったに起こらないこと」として扱い、無視を決め込んでいる。

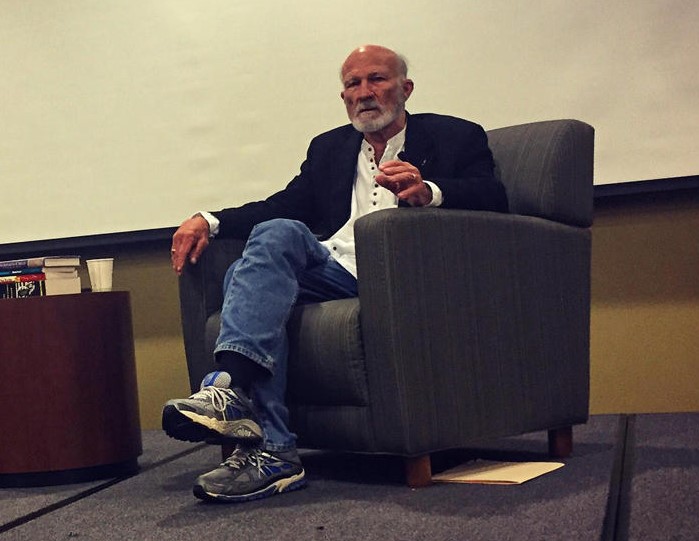

スタンリー・ハワーワス(写真:Benjamin Payne)

倫理学者であり神学者でもあるスタンリー・ハワーワスは次のように述べた。

[toggle]And while the talk of quarantine is certainly unsettling, we might remember that it has been commonplace for some time to sequester the ill. Indeed, we already isolate the dying in hospitals and often permanently displace them in nursing homes. We live in the midst of an epidemic of loneliness that already leads to adverse health outcomes. When real life-threatening illnesses arise, we shouldn’t be surprised that we have no idea what to do. We haven’t practiced for it. We haven’t raised our children around it. Ours is a culture that treats death and physical suffering as an exception to ignore rather than an eventuality to prepare for. Ethicist and theologian Stanley Hauerwas puts it this way: [/toggle]「究極的に言えば、病院は何よりも、私たちが旅の途中で立ち寄る『もてなしの家』です。私たちが私たちである証拠は、『病にかかった人を見捨てない』ということです。……現代の病院の多くがそうであるように、病人をほかの人々から遠ざける手段となってしまっているのであれば、私たちは病院の存在意義を裏切り、コミュニティーのあるべきかたち、私たち自身のあるべきかたちから離れているのです」

[toggle]The hospital is, after all, first and foremost a house of hospitality along the way of our journey with finitude. It is our sign that we will not abandon those who have become ill. … If the hospital, as too often is the case today, becomes but a means of isolating the ill from the rest of us, then we have betrayed its central purpose and distorted our community and ourselves. [/toggle]形而上詩人のジョン・ダンは、「病にかかることは苦しみの極み、病の最大の苦しみは孤独」と書いた。私たちがどのような防疫対策を行うにせよ、この「社会的距離」の時代が終わった後、私たちが戻るのはこの孤立の時代であることを覚えておいたほうがいい。もしかするとこの疫病の大流行は、私たちに現実を見させてくれたのかもしれない。新型コロナ・ウイルスによって私たちが自分の家に閉じこもるずっと前から、私たちは「孤立」という病にかかっていたのだ。

[toggle]The metaphysical poet John Donne wrote, “As sickness is the greatest misery, so the greatest misery of sickness is solitude.” Whatever practices of social quarantine we undertake, we would do well to remember that our era of isolation will remain once this practice of “social distancing” fades. Perhaps this pandemic is a chance to wake us up to the reality that we have been surrounded by the isolated ill long before the new coronavirus found us staying at home. [/toggle]一方、「社会的距離」は、教会が慈善と勇気の精神をもって実行できる対策だ。私たちは愛をもって、この弱者を守る対策のために協力することができる。そのために私たちは、疫学の知識と実用的な知恵、そして謙虚さを組み合わせる必要がある。

[toggle]At the same time, social distancing is something the church gets to perform charitably and courageously. It is a literally corpor-ate (“bodily”) duty that we have the opportunity to enact out of love to protect the vulnerable among us—in which we partner infectious disease science with practical wisdom and humility. [/toggle]高齢者や弱者、障害者など、社会的に孤立しがちな人々との「社会的同伴」を実践するのに必要なのは創造性だ。病床にある人に対しては、保護衣を着た状態で聖餐を行ってもいい。特別養護老人ホームの人々は、これからさらに孤立させられるだろう。それならば私たちは、その人々に電話をかけたり、祈りの手紙を書いたりすることができるのではないか。私が通う教会の牧師の一人は、信徒席との距離を離すことを希望している。除菌対策は毎週の聖餐式でお手のものだ。

[toggle]We get to be creative in how we reach out and practice “social accompaniment” to those who are already prone to social isolation: the elderly, infirm, and disabled. We might bring the Eucharist to the sick in protective garb, make calls to those in nursing homes (who will become increasingly isolated as visits are limited to those communities), and write letters of prayer. One of our own pastors hopes to arrange congregants at a distance while continuing to practice the sterility that priests are already well familiar with as they handle weekly Communion. [/toggle]クリスチャンとしての想像力を働かせると、見えてくる工夫もある。ある医学生のアイデアはその一つだ。その学生は、カトリックの司祭が聖体を扱う時に行う、手を清める所作を真似しながら、手指消毒液で除菌をしたのだ。彼はこの神学的な見方を通して、病人のただ中にいるキリストと会う準備をしたといえる。

[toggle]When we put Christian imagination to work, we discover practices like that of a medical student who participated in the Physician’s Vocation Program, created by John Hardt at Loyola University Chicago. As Christian ethicists Brett McCarty and Warren Kinghorn describe the student: “Instead of mindlessly applying the hand sanitizer, he instead pictured his Catholic priests washing their hands in preparation for handling the Eucharist. … Through this theological vision, he prepared to meet Christ in the body of a sick patient.” [/toggle]不安の中の嘆き

[toggle]Lament Among Anxiety[/toggle]世界の人々は、スポーツ・イベントの中止や経済の停滞を嘆いている(そういったことに落ち込むこと自体は間違ったことではない)。私たちも新型コロナ・ウイルス、そしてそれに対する自らの対応(社会的距離)によって、教会が本来の姿を失ってしまったことを知っている。私たちが社会的距離を取らなければならないのであれば、そこには嘆きがあるべきだ。

[toggle]While the world laments the cancellation of sporting events or the halting of the economy (all appropriate things to be dispirited about), Christianity recognizes that both the new coronavirus and our response to it through social distancing makes the church something less than its full self. If social distancing is something we must do, we shouldn’t do it without psalms of lament. [/toggle]そして嘆くことは、今後数週間でますます重要になるだろう。(おそらく北米に最も近い医療システムである)イタリアの医療は、ICUに収容された患者との接触を家族に制限した。その患者が死んだ後、ほとんどの家族は遺体と面会することができない。イタリアで集中治療医をしている同僚に聞く限り、私たちも「それぞれの患者にとって何がベストか」ではなく、「コミュニティー全体にとって何がベストか」を優先させる必要に迫られるかもしれない。それは、通常ならあらゆる治療を行うことができていた私たちにとって非常に心苦しい事態だ。あらゆることが大いなる悲嘆と疲労感をもたらす可能性がある。

[toggle]And lament will become increasingly important in the coming weeks. Medical workers in Italy (perhaps North America’s closest comparable health care system) have greatly limited family interactions with the sick in the ICU. Most families cannot view the bodies of their loved ones after death. As we’re learning from our Italian intensivist colleagues, we may find ourselves unable to do what is best for each patient, and instead must balance what is best for the entire community—something that greatly troubles those of us in medicine used to being able to do all that is possible. All of this has the potential to lead to great grief and exhaustion. [/toggle]

茨の冠(写真:Simon Speed)

このタイミングで私たちがレントを迎えたのは不思議な気がする。イースターを迎える時、私たちは大きな石が取りのけられた墓だけでなく、扉の開かれた大聖堂という新たな希望を持つべきなのかもしれない。新型コロナ・ウイルスの時代の受難週。今、ゴルゴタに向かう王の苦しみを覚える時、そこには確実にこれまでと違う意味合いがあるはずだ。

[toggle]It is uncanny that we are in the season of Lent. Perhaps we should look to Easter Sunday with newfound hope, not only of open tombs but of reopened cathedrals. Holy Week in the time of COVID-19—in which we remember the suffering of the King on his way to Golgotha—will surely take on new meaning. [/toggle]興味深いことに、「コロナ」という名前は、このウイルスのもつスパイク状のタンパク質の輪が冠に似ていることから名づけられた。多くの点で新型コロナ・ウイルスは、私たちがあがめていたものを明らかにした。それは「健康」であり「自己防衛」であり「医学」だ。世界中の人々が新型コロナ・ウイルスに注視し続けるのは、私たちがそこに「不安」と「支配」、そして「恐怖」を見るからだろう。

[toggle]Indeed, it is interesting that the coronavirus gets its name from a spiked ring of proteins on its surface that resembles a crown, hence the title of “corona.” In many ways, the coronavirus is revealing the crowned heads we already worship—health, self-protection, medicine. Our global, sustained attention to COVID-19 demonstrates that which we look to out of anxiety, control, and fear. [/toggle]もちろん私たちは、イエスがかぶせられた冠がコロナのそれとは違うことを知っている。イエスの冠が私たちに呼びかけるのは、不安や支配から起こされる崇拝ではなく、すべての恐れを解き放つ愛から起こされる崇拝だ。イエスの冠によって、この新型コロナ・ウイルスの脅威が弱まるわけではない。しかしそれは、私たちが誰に不安を訴えるべきか、誰を慰めるべきか、そしてどの冠のことを覚えておくべきかを教えてくれる。

[toggle]Of course, we know that Jesus wore a different crown—one that calls us to worship not out of anxiety or control but out of a love that drives out all fear. That crown doesn’t make this coronavirus moment any less serious; however, it does tell us where to cast our anxieties, who to comfort, and which thorned crown to remember. [/toggle]執筆者のブリューアー・エベリーは、サウスカロライナ州アンダーソンにあるアンメッド・ヘルス・メディカル・センターのかかりつけ医(1年目)。ベン・フラッシュは、ナッシュビルにあるヴァンダービルト大学医療センターの内科、およびモンロー・キャレル・ジュニア小児病院の小児科内科医(2年目)。エミー・ヤンは、シナイ山にあるアイカーン医科大学の医学生。(4年目)3人はそれぞれデューク神学校で神学、医学、文化フェローシップを修めている。本記事の見解は著者の見解であり、必ずしも出身機関の意見や方針を表すものではない。

本記事は「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(米国)より翻訳、転載しました。翻訳にあたって、多少の省略をしています。