現代の「不安感」

[toggle]I am a millennial statistic. Dubbed “the anxious generation,” most of us are stressed, and we experience work-disrupting anxiety at twice the average rate. We are leaders of the mental health crisis in a world where many think anxiety is generally on the rise.Until recently, I didn’t think I was an anxious person. Then, in a single year, I finished writing my PhD thesis in England, worked multiple part-time jobs to pay the bills, tore my MCL (with a wife 36 weeks pregnant), became a first-time father, found an academic job, got a work visa, moved across the Atlantic, found housing, completed my first term of teaching, and defended my doctoral thesis. By no means was all of this bad or world-ending—some of it was very good. But at the end of it all, I was burned out and anxious.

My story isn’t unique. Workplaces are increasingly mobile, creating the risk of isolation and overwork. Young people are told to go anywhere and do anything, but their mental health is paying the price. And that’s to say nothing of weightier problems like addiction, abuse, chronic illness, joblessness, homelessness, and a host of others that afflict so many today. A thriving wellness industry has risen in response, complete with Instagram therapists, wellness dogs, and stress-relief toys. As a Christian, you can feel tension—even guilt—when a doctor or a self-help book improves your mental health more than a Bible reading. [/toggle]

私はいわゆる「ミレニアル世代」(訳注:2000年付近生まれの世代)の統計学者だ。私たちの世代は「不安な世代」、ストレスを感じやすい層とされ、仕事に影響が出るような不安感を抱いている率は全体平均よりも2倍ほど高い。現代社会では総じて不安感が高まっていると言われているが、そのなかでも私たちはメンタルヘルス問題の先頭を走っている。

最近まで、私は自分のことを不安定な人間だとは思っていなかった。当時、私はイギリスでの博士論文を1年の間に書き終え、生活費を稼ぐために幾つもアルバイトを掛け持ち、妻が出産を控えたタイミングだというのに大きな怪我を経験し、初めての父親になり、学者としての仕事を見つけたところだった。そして就労ビザを取得し、大西洋の反対側に引っ越し、住まいを見つけ、初めての学期を乗り越え、博士課程を修了させた。これらのことが悪いものだったとか、絶望させるようなものだった、というわけでは決してない。非常に良かった出来事もあった。しかしすべてが終わったときに残ったのは、燃え尽きて不安を抱えていた自分だった。

これは私だけに起こったことではない。職場の改革が進む中で、多くの人が孤立と過労のリスクと隣り合わせになっている。若い人は好きなところに行って好きなことをしたらいい、と言う人もいるが、その代償となっているのは私たちのメンタルヘルスだ。依存症や虐待、慢性疾患、失業、ホームレス状態などに苦しんでいる人も多い。

結果として健康産業は栄えた。世にはインスタグラム・セラピストや癒しをもたらすペット、ストレス解消器具などが流行している。医師や世の知恵を教える本が、聖書朗読以上に私たちの心を癒しているのだ。クリスチャンとしてはちょっと後ろめたいような気持ちにもなる。

様々な不安感と旧約聖書

[toggle]As someone who has sought professional help for anxiety, I can say that my own recovery has always been rooted in the Bible, especially one Old Testament passage: “Do not fear, for I am with you; do not be dismayed, for I am your God. I will strengthen you and help you; I will uphold you with my righteous right hand” (Isa. 41:10). If you accept the wisdom of the media, or even of some Christian leaders, my deliverance shouldn’t have happened this way—not with the help of that dry, dusty Old Testament. But as others buy a casket and recite a eulogy for these texts, I find them bounding with life.Thankfully, I’m not the only one. Many of our most therapeutic worship songs brim with Old Testament references, including “Raise a Hallelujah” and “Blessed Be Your Name.” Fleming Rutledge’s award-winning book The Crucifixion notes how communities that endure generations of marginalization find solace in Old Testament stories of exile and deliverance. This is seen in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, in which King employs Old Testament themes, including an allusion to Psalm 30, to comfort his anxious audience.

The texts of the Bible—especially the Old Testament—are ancient, and they were written long before our mental health crisis. But they’re neither irrelevant to our concerns nor merely a backstory to the more useful New Testament. In fact, by telling the stories of various individuals and their toughest experiences, the Old Testament is not so ancient—it delivers a special form of group therapy. [/toggle]

心療内科に世話になってきた一人の人間として言うが、精神が落ち着くとき、私の心にはいつも聖書、特に旧約聖書に書かれた一節があった。

恐れることはない、わたしはあなたと共にいる神。

たじろぐな、わたしはあなたの神。

勢いを与えてあなたを助け

わたしの救いの右の手であなたを支える。(イザヤ書41章10節)

メディアの言うことや一部のキリスト教指導者の言う事に振り回されていたら、わたしは心の平安を得ることは出来なかっただろう。

人々は旧約聖書のことを水気が失われてほこりっぽくなった書物のように扱っている。そしてこの書物を葬るかのようにして、中に書かれた煌(きら)びやかな文言を弔辞代わりに唱えているが、私にとって旧約聖書とは生命力に満ちあふれた書物だ。

嬉しいことに、そのように考えているのは私だけではない。

私たちが好んで歌うワーシップソングの多くは旧約聖書に基づいた癒しのメッセージを伝えているし、著名な本『十字架(The Crucifixion)』は、何世代にもわたる差別にあえぐ人々が出エジプト記の解放物語に慰めを見いだす姿を伝えている。

「私には夢がある」と語ったスピーチの中で、キング牧師は詩篇30章に触れつつ、不安に苛(さいな)まれている聴衆を慰めた。

聖書のなかでも特に旧約聖書の起源は古い。

この書物は私たちがメンタルヘルスの危機にさらされている現代よりもずっと前に書かれたものだ。

しかしその物語は私たちの不安感から遠く離れたものではないし、ただの「新約聖書・裏ストーリー」でもない。

多様な人々の物語、そしてそこにある困難を語る旧約聖書は、実際のところそれほど古めかしいものではない。いうなれば、それは(時を超えた)特殊なグループ療法の一種なのだ。

旧約聖書に描かれる不安感

[toggle]The relevance of the Old Testament for addressing anxiety begins with its composition. It is the product of dozens of authors over a whole millennium. So it catalogs an overwhelming number of traumatic events, from the murder of Abel and Israel’s oppression in Egypt to the rape of Tamar and the exile to Babylon, to name just a few. This is different from the New Testament, which is so focused and was finished so quickly that similar first-century events—the destruction of the temple or the eruption that leveled Pompeii and may have killed dozens of early Christians—are not recorded.Imagine you’re standing near the site of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. What thoughts and feelings would you experience? Almost all Americans who were alive during the attacks remember where they were on that fateful day and what it felt like to watch the news repeatedly show the buildings’ collapse. The experiences undergirding the Old Testament texts aren’t much different. At least one disturbing event for society at large—from natural disaster or military invasion to national exile or political scandal—lies behind almost every Old Testament writing.

It’s no surprise, then, that the Old Testament is more saturated with the Bible’s famous “fear not” statements than the New Testament. These documents distill the wisdom of centuries, ushering us into the counsel of the eldest elders and the wisest sages to learn what it means to trust in God. [/toggle]

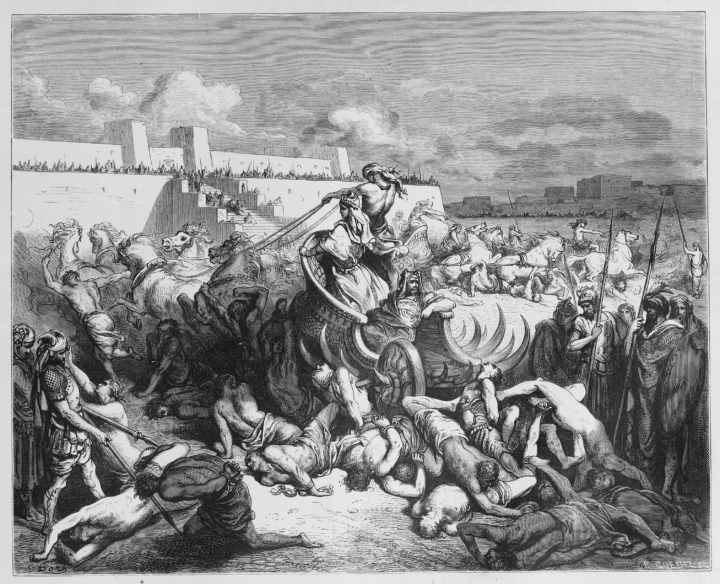

「旧約聖書が私たちの不安感にどのようにつながっているのか」を考えるときに、まず目を向けるべきはその構成だ。旧約聖書は、数千年にわたって何十人もの著者によって書かれた。そこにはアベルの殺害やエジプトにおけるイスラエル民の弾圧、タマルの強姦やバビロン捕囚など、読むものを圧倒させるようなトラウマ的出来事が羅列している。これは新約聖書には見られないものだ。新約聖書は一点集中型の作りになっており、終わり方もあっけないため、1世紀に起こった出来事(神殿の破壊や、大勢のクリスチャンを殺したであろうポンペイ噴火)などの記録も見られない。

想像してみてほしい。たとえば、あなたが2001年9月11日に世界貿易センターの近くにいたら、どのような考えや感情を体験するだろうか?テロを生き延びたほとんどの人は、その日自分がいた場所のことや、ニュースで繰り返し流されるビルの崩壊を見た時の感情を明瞭に覚えている。旧約聖書には、それと同じような経験をした人々の想いが根底にある。ほぼすべての旧約聖書の物語には、自然災害や軍事的侵略から国外追放または政治スキャンダルまで、社会全体を脅かすような様々な事件が背景にある。

そう考えると、旧約聖書が有名な「恐れてはならない」といったメッセージで満ちていることは驚くほどのことではない。この書物には何世紀にもわたって受け継がれてきた知恵が積み上げられおり、長老や賢人たちの助言に従って、神を信頼することの意味を知るよう私たちに勧めている。

(続く)

著者のB.G. ホワイト氏はニューヨーク市にあるキングズカレッジの助教授(聖書学)、牧師。神学者センター・フェロー。

本記事は「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(米国)より翻訳、転載しました。翻訳にあたって、多少の省略をしています。

出典URL:https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2019/november-web-only/neuroscience-and-scripture-agree-it-helps-to-lament-in-comm.html?fbclid=IwAR0wsNJdWrveRHsfALI-MTmPJ_jHNXPI1wQkcMT8OsP3sZWIgZ1qgZ8YInA