ゴシック建築は古くから、宣教師がたどり着けなかった非信者の心とたましいと共にあった。ノートルダム大聖堂の炎上を悲しむ世界中の声は、この建物がどれだけ大きな影響力を持っていたかを明らかにしている。

[toggle]Gothic architecture has long reached where Christian missionaries would go but are not permitted: the minds and hearts of the faithless. The world’s grief over the flames at Notre-Dame de Paris revealed its power as far more than architectural style. [/toggle]

(写真:Wandrille dePréville)

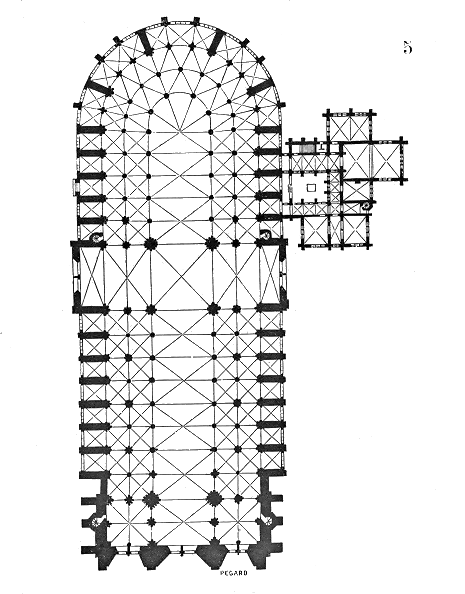

中世の偉大な評論者、ウィリアム・デュランティスは、このゴシック教会がキリストの体をかたどっているという。建物の内陣はキリストの頭、翼廊(よくろう)は腕、そして祭壇は心臓だ。この教会がキリストの体を象徴しているとすれば、今週の月曜日(15日)にノートルダム大聖堂が燃え上がるのを見たことは、予定より早く訪れた聖金曜日(受難日)の経験ともいえる。

[toggle]For the great medieval commentator William Durandus (d. 1296), the Gothic church took the shape of Christ’s body: the chancel the head, the transepts the arms, the altar the heart. And if the Gothic church symbolizes the body of Christ, to see Notre Dame burn this Monday was to experience Good Friday early. [/toggle]

尖塔が燃え落ちる様子は、見るに堪(た)えないものだった。ただ、(こう言うのは気が早いかもしれないが、)パリのノートルダム大聖堂に代表されるゴシック様式は、火事で終わってしまうようなものではない。ゴシック様式は教会にガラス芸術や石細工の神学をもたらし、何世紀にもわたって世界中のカトリックとプロテスタント建築の一つの模範として広がった。

[toggle]It was excruciating to watch its spire fall. But at the risk of saying this too soon, the Gothic style represented by Notre-Dame de Paris cannot be stopped by fire. This style has given the church a theology of glass and stone, a model that has spread to Catholic and Protestant structures across the centuries and around the world. [/toggle]

シャルトル大聖堂(写真:MathKnight)

パリから南西に約50マイル(87キロ)離れた場所にあるシャルトル大聖堂は、ゴシック様式の大聖堂の中で最も完成度が高いものだが、もともと火災によって生まれた建物だ。火災は1020年、1134年、94年に起こり、そのたびに再建された。歴代フランス国王の戴冠式が行われたランスのノートルダム大聖堂(パリから東北東約130キロに位置する)のこまやかな石細工も同様に、1208年の火災のあとで作られたものだ。ゴシック建築は陶器細工のように、炎とは相性がいい。

[toggle]Fifty miles from Paris, the greatest and most complete of Gothic cathedrals, Chartres, was itself born of fire, built and rebuilt after blazes in 1020, 1134, and 1194. It is no different with the delicate stonework of Reims, France’s great coronation cathedral—the result of a fire in 1208. Gothic architecture, like the art of pottery, does quite well with flames. [/toggle]

サン・ドニ修道院(写真:MOSSOT)

ゴシック建築は12世紀半ば、パリ北部のサン・ドニ修道院で編み出された。「当時のシュジェール大修道院長による建築改革は、(米国でいえば)新しい大統領が、近代建築の巨匠フランク・ロイド・ライトのスタイルでホワイトハウスを造り直すようなものだ」と芸術史家エルヴィン・パノフスキーは評している。大胆なリスクをとった彼の建築計画は、みごとに成功を収めた。

[toggle]The Gothic style first emerged in the mid-12th century at the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis just north of Paris. Abbot Suger’s innovation there was the equivalent, the art historian Erwin Panofsky once commented, of a new president remaking the White House in the style of Frank Lloyd Wright. And his bold architectural risk paid off. [/toggle]ゴシック建築に神学的・典礼的な影響があったことについては、明白な証拠がある。「精神に光をもたらし、まことの光を通して旅をさせ、真実のドアであるキリストを通って真実の光へとたどり着けるように」という意図が、サン・ドニの扉には注意深く刻み込まれている。採光の目的は、照らすことではなく、それを見る者に伝道することだった。

[toggle]The plain evidence for Gothic’s theological and liturgical inspiration is unavoidable. Over the door of Saint-Denis, Abbot Suger carefully inscribed the purpose of the new illumination from the cathedral’s windows: “To brighten the minds, so that they may travel, through the true lights, To the True Light where Christ is the true door.” The point of the light was not just to dazzle, but to evangelize. [/toggle]

(写真:PMRMaeyaert)

またこれは、足が地についていない空虚な神秘主義でもない。セメントの材料でさえ神学的な意味合いが込められている。デュランティスによれば、石灰は「愛」、砂は「この世における憐れみ」を意味する。そして、セメントを作る3つ目の材料は、「聖霊」を指し示す水だ。信者の良い働きも、水なしには無益となる。

[toggle]Nor was this an airy mysticism devoid of contact with the earth. For goodness’ sake, even the ingredients of the cement bore theological weight. For Durandus, the lime is love, the sand temporal works of mercy. Neither makes cement without the third ingredient, water, which points to the Holy Spirit, without whom the good works of the believer are in vain. [/toggle]

ノートルダム大聖堂 のフライング・バットレス(写真:Lusitana)

サン・ドニ修道院に続いて、人々に愛される様式がノートルダム大聖堂で初めて生まれた。これは芸術史用語で「フライング・バットレス」(空中にアーチを架けた飛梁)と呼ばれる。身廊に追加されたこの部分により、外側から建物の重さが支えられ、より多くの光を取り入れられる大きな窓を作ることが可能になった。まるで巨大な蜘蛛(くも)がバラ窓(ステンドグラス)を繊細な手つきで編んだあと、建物の上で休んでいるかのように、フライング・バットレスは建物全体を包み込んでいる。この新しいアイデアは大きな成功を収め、ライバル格の大聖堂(マントラジョリ、ランス、カンタベリー、ラン)は急ぎそれに倣(なら)った。

[toggle]Following Saint-Denis, Notre-Dame de Paris gave us the first example of everyone’s favorite art historical term: the flying buttress. These addendums to the nave projected more weight outwards, permitting larger windows that let in more light. The buttresses envelop the structure as if a massive spider were resting after delicately weaving the rose windows. The flying buttress innovation was so successful that rival cathedrals (Mantes, Reims, Canterbury, Laon) scrambled to follow. [/toggle]イタリアの美術史家ジョルジョ・ヴァザーリは、「そのような建築様式にイタリアが浮かれることはない」と憤慨し、 「フランス人の作品(opus francigenum)」と呼ばれたこの様式を、野蛮なゴート族になぞらえて「ゴシック(ゴート風の)」と嘲笑した。しかし、「印象派」や「キュービズム」などと同様、見下すようなあだ名をつけたところで、この流れを止めることはできなかった。

[toggle]The Italian art historian Giorgio Vasari, vexed that Italy never rose to such architectural heights, mocked the style—then known as the opus francigenum (French work)—as that of the barbarian Goths. But as with famous insults like “Impressionism” or “Cubism,” the term “Gothic” stuck, but it could not stop a movement. [/toggle]

ウェストミンスター寺院(写真:Ed g2s)

ヨーロッパでルネサンスが芸術と建築の世界に起こると、ゴシック様式の影響はほぼ消滅した。しかし、探求が続けられた中世イギリスでは、エセックス、ウェストミンスター、ウェールズなどで大きな成功を収め、その影響が消えることはなかった。やがて18世紀には、静かな庭園の別館にも尖(とが)ったゴシック様式が用いられるようになり、尖塔のついた英国の城は、バロック文化とは異なる装いをまとった。

[toggle]The emergence of Renaissance art and architecture in continental Europe nearly extinguished the style’s influence, but Gothic embers kept burning in England, where the great medieval experiments at Essex, Westminster, and Wells in England were too successful to fully suppress. In time, pointed Gothic pavilions crept into quiet 18th-century gardens, pinnacled castles sprung up to distinguish Britain from the Baroque. [/toggle]19世紀には、信心深い建築家オーガスタス・プージンやケンブリッジ大学教会学協会に属する優秀な学生たち、初期オックスフォード運動の楽観主義、そしてヴィクトル・ユーゴーとジョン・ラスキンの影響力により、ゴシック様式は燃え上がるようにして勢いを取り戻した。

[toggle]In the next century, the religious fervor of architect A. W. N. Pugin, the principled and pugnacious undergraduates of Cambridge’s Ecclesiological Society, the optimism of the early Oxford Movement, and the infectious pens of Victor Hugo and John Ruskin all brought the Gothic style back to a roaring flame. [/toggle]

ノートルダム大聖堂の尖塔(写真:Pedro Szekely)

しかし、当時の用いられ方がすべて神学的な示唆を含んでいたわけではない。ゲーテはゴシックに「不可解な一体感」を覚えざるを得ず、フランスの偉大な修復家ウジェーヌ・エマニュエル・ヴィオレ・ル・デュクは、この様式の構造に聡明さと合理性を見た。ウジェーヌがノートルダム大聖堂を修復する際に付け加えた尖塔は、この月曜に崩壊した。これは悲劇には違いないが、今後、ゴシックの基本、宗教的な核心への回帰点としてこの出来事が理解されるかもしれない。

ウールワース・ビルディング(写真:Martin Furtschegger)

ニューヨークのウールワース・ビルディング、シカゴのトリビューン・タワーといった商業化されたゴシック建築は、結局のところ完全なものではなかった。マイケル・J・ルイスが言うように、ゴシック様式を活かすには、「陳腐なスピリチュアル集団の残りかす」に忍耐しているようではだめなのだ。

[toggle]Not all of its new uses were theologically inspired. The Gothic could provide an “inexplicable feeling of oneness” for Goethe, while the great French restorer Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (d. 1879) saw in the style a cool, structural rationality. Perhaps Monday’s collapse of the spire he added to Notre Dame—calamitous as it was—might even be understood as a return to the Gothic’s foundational, religious core. The commercial Gothic of the Woolworth Building in New York and the Tribune Tower in Chicago, after all, have never been entirely convincing. As Michael J. Lewis puts it, Gothic needs far more than “a residue of vapid spiritual associations” to endure. [/toggle]

トリニティ教会

やはり、この建築様式とキリスト教とは深く結びついている。国民のほとんどをプロテスタントが占める米国でも、壮大なカトリック建築に対抗しようと、プロテスタント諸教派がこの様式を受け入れ、繁栄した。マンハッタンでリチャード・アップジョンのトリニティ教会やジェームズ・レンウィック・ジュニアのグレース・エピスコパル教会の完成が祝われた時期のことだ。

ニューヨーク教会学会はゴシック主義者を厳しく批判したが、それは彼らを逆に優位な立場に立たせることになった。メソジストやバプテストなど、カトリック文化に距離を取っていた教派でさえ、尖ったアーチの魅力には抗(あらが)えなかった。そのようにして米国のプロテスタント信者とカトリック信者は神学的な違いを持ちつつも、トレフォイル(ゴシック建築の窓の装飾に使われる三つ葉のデザイン)やトレーサリー(同じく幾何学模様の装飾)、そして翼廊によって一つとなった。

[toggle]But the style’s rich connection to Christianity is what enabled it first to thrive in a mostly Protestant America, as rival denominations sought to compete with majestic Catholic buildings, eradicating any lingering Puritan suspicions. These were the years where Manhattan welcomed Richard Upjohn’s Trinity Church and James Renwick Jr.’s Grace Episcopal Church. The New York Ecclesiological Society goaded Gothicists to excellence with stinging criticism. Even denominations traditionally suspicious of high-church culture—Methodists and Baptists—were unable to resist the pull of the pointed arch. And so it was that American Protestants and Catholics, divided by theology, were unified by trefoils, tracery, and transepts. [/toggle]その結果、数十年のうちに尖塔が国有林のように建ち並んだ。「ゴシック様式の尖塔が大量の矢のように打ち上げられた。世界は覚醒したのだ」と、ヨーロッパの13世紀についてチェスタトンは記したが、19世紀以降の米国でも同様のことが起きた。それはさながら、全世界がゴシックの肌をまとっているようだった。中国やインド、インドネシア、ブラジルには、素晴らしいゴシック様式の建築が自らの環境に適応したかたちで存在している。

[toggle]The result was a national forest of spires built in a few decades. “It was the Gothic going up like a flight of arrows,” wrote Chesterton of Europe’s great 13th century, “it was the waking of the world.” A similar waking happened in America as well in the 19th century and beyond. The entire globe, in fact, has Gothic skin. There are handsomely Gothic structures in China, India, Indonesia, and Brazil, each adapted to their own environments. [/toggle]

中国の石室聖心大聖堂(写真:Zhangzhugang)

クリスチャンにとってゴシックは、男性にとってのスーツとネクタイのようなもので、機能的で柔軟な正装といえる。ノートルダム大聖堂の火事は、ゴシックの存在を失わせるものではない。スーツ量販店の本部に火事が起きたからといって、ネクタイの存在がなくならないように。

[toggle]Gothic is to Christian building what the suit and tie is to menswear—functional, appropriate, flexible. A fire at Notre Dame cannot stop this any more than a fire at Men’s Wearhouse corporate headquarters can undo the necktie. [/toggle]

第4長老教会(シカゴ)

ここで私の個人的な話を紹介したい。現在、シカゴ美術館で展示されているノートルダム大聖堂の「使徒の頭」(全身彫刻の柱の一部)の下を、2日前、ホイートン大学の約200人の学生とスタッフが見て歩いた。シカゴには、聖ジェームズ大聖堂や第4長老教会、ホーリーネーム大聖堂など、ノートルダムの影響を受けた建物が栄誉の証しとして点在している。妻からノートルダム崩壊のニュースを聞いた私は、すぐにミシガン州のグランドラピッズに向かった。そこの街並みは、ノートルダムに直接的な影響を受けた尖塔によって守られている。同様の光景は世界各地で見られる。

[toggle]Take these personal anecdotes as illustrations: Two days ago nearly 200 students and staff of Wheaton College walked under a head of an apostle from Notre-Dame de Paris at the Art Institute of Chicago, a city where Notre Dame’s influence—through St. James Chapel, Fourth Presbyterian, or Holy Name Cathedral—affords graceful epaulettes to the city of broad shoulders. And just after my wife called me to tell me the news of Notre Dame’s destruction, I drove into Grand Rapids, Michigan, where I saw several Gothic spires, directly indebted to Notre Dame, guarding this American skyline, as they do in cities throughout the world. [/toggle]1世紀前、エミール・マールはゴシック建築についてこう書いている。「自分が何かの影響を受けていることを認めようとしない現代人でさえ、(ゴシック建築の前に立つと)深い静けさを覚える。そして、自らの疑問や理屈からしばし離れることができるのだ」

[toggle]A century ago, Émile Mâle wrote this about Gothic architecture: “Even the modern man receives a deep impression of serenity, little as he is willing to submit himself to its influence. There his doubts and theories may be forgotten for a time.” [/toggle]燃え上がるノートルダム大聖堂を見た世界の反応は、マールの洞察を裏づけるものだ。ゴシックはキリスト教信仰の永遠の表現であり、決して失われることはない。それは少しの間、姿を見せなくなるだけだ。そして、次の日曜日によみがえったキリストのように復活するだろう。

[toggle]The global reaction to the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris burning yesterday confirmed Mâle’s insight. But as a perennial expression of Christian faith, Gothic never dies; it only rests for a while. And like Christ this coming Sunday, it will rise again. [/toggle]執筆者のマシュー・J・ミリナーは、ホイートン大学の美術史の准教授。ツイッターアカウントは @millinerd。

本記事は「クリスチャニティー・トゥデイ」(米国)より翻訳、転載しました。翻訳にあたって、多少の省略をしています。